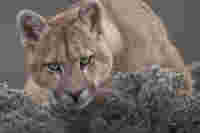

My tracker and I have been following the male puma Charqueado for half an hour. He is four years old, so fully grown, and a fine specimen. After lounging in the morning sunshine for a while, he gets up and looks around for a sleeping place where he can spend the day. Around 40 meters (131 feet) away from us, he walks toward a little hollow in the ground that is overgrown with shrubs. We follow. For a fleeting moment, we lose sight of him and this is all it takes, he already seems to have been swallowed up by the earth. We spend a whole hour scanning the hip-high mata negra scrub for him using binoculars but despite our best efforts, we fail to locate him again. It suddenly crosses my mind that I have walked through similar overgrown hollows many times before. It would be so easy to come across a puma here without spotting it in time. I felt a cold shiver run down my spine.

This situation is a good example of just how clever pumas can be at concealment. The ability to make itself invisible is crucial for a puma’s survival – especially in the Torres del Paine region where the felines hunt mainly the ever-alert guanaco. These large herbivores from the llama family have set up watchposts everywhere to look out for danger and give a warning call that resonates far into the distance as soon as they spot anything suspicious. Guanacos are very fast so pumas need to mount a stealth attack at close quarters, otherwise they don’t stand a chance. The guanaco’s warning call heralds the end of the hunt before it has even had a chance to get started. Every animal in the vicinity is then aware of the hunter’s presence. However, thanks to the puma’s typical feline jumping power and agility, when close enough to its prey, it can overpower animals far in excess of its own body weight.

Six different subspecies of puma are distributed throughout North and South America. In the past, they inhabited almost every area of America, but their numbers have now declined sharply. This is mainly due to illegal hunting and the increasing destruction of their natural habitat. Total numbers are estimated at below 50,000. According to current estimates, there are still 60 to 100 pumas in the Torres del Paine National Park. Taxonomically, this feline species is not a big cat, although it is the fourth-biggest wild feline in the world. Fully-grown males can measure up to two meters (6.5 feet) from nose to hindquarters and weigh as much as a hundred kilograms (220 pounds). Females are slightly smaller and lighter. Pumas have large paws and the strongest rear legs of all felines. From standing, they can jump up to five meters (16 feet) in the air and leap forward over a distance of twelve meters (39 feet). In full sprint, they can reach a top speed of 80 kilometers (50 miles) per hour. Female pumas roam over an area of around 25 square kilometers (9.6 square miles) in the Torres del Paine National Park, where food supplies are plentiful, while males sometimes cover distances of over 60 square kilometers (23 square miles).

About the Author

Puma Land

Ingo Arndt was born in Frankfurt am Main, Germany. From early childhood, he spent every single minute of his spare time outdoors in nature. Soon he realized that photography was a useful tool in environmental protection, so, after finishing school in 1992, Ingo plunged into the adventurous life of a professional photographer. Since then, he has traveled around the globe for extended periods as a freelance wildlife photographer, photographing reports in which he portrays animals and their habitats. In the past few years he has been mainly on assignment for GEO and National Geographic Magazine. With his images, Ingo wants to stimulate and increase the awareness of his viewing audience and show them the magnificence of nature.

His adventures with the pumas in Torres del Paine National Park have also been published in the book PumaLand (2019).